The UK Government’s intention to enforce the wearing of masks on public transport is not only without legality, therefore, but it also has no proven basis in medical science. It is, rather — as the World Health Organisation’s revised advice on 5 June suggests — a means of enforcing further compliance with lockdown measures that have already condemned this country to what the Bank of England has predicted will be the worst depression in over 300 years, pushed unemployment to exceed an estimated 3 million, bankrupted thousands of small businesses, and caused the death of thousands of British citizens through the unnecessary and irresponsible cancellation of life-saving medical treatment, all while the Government sells our personal medical data to US tech firms, outsources our National Health Service to private companies, and in the absence of parliamentary scrutiny or approval makes legislation and regulations in violation of our human rights and civil liberties.

4. Surveillance and Compliance

There are other countries in which the wearing of masks has become customary, if not yet mandatory. Japan has a long history of wearing masks, going back to the so-called Spanish flu of 1919, the global flu epidemic of 1934, and the rise in pollution levels in the 1950s during rapid industrialisation. However, following the outbreak of SARs (severe acute respoiratory syndrome) in 2002, the panic around avian influenza in 2006, and the Ebola epidemic in 2014, wearing masks in public has become an increasingly-expected and enacted civic duty in China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, and the recent influx of East-Asians into London in particular has brought the practice to the UK. We should recall that since 2002 SARs has killed a reported 774 people worldwide, bird flu 616, and Ebola over 11,000 people, almost entirely in West Africa; so the uniform wearing of masks in public among the 1.677 billion population of East Asia is out of all proportion to the actual threat of infection.

We would be wrong, however, to see the wearing of masks as only a matter of convention that should be uncritically imported into the UK as part of our response to the coronavirus crisis. In many East Asian countries the wearing of masks in certain public places such as hospitals and schools was made mandatory by their governments long before the coronavirus crisis, and Western observers have not been blind to their role in normalising and encouraging compliance with other measures of population surveillance and control. On 6 April, in an article titled ‘Coronavirus and the Future of Surveillance’ published first in Foreign Affairs (a forum for discussion of US foreign policy) and then in Belt & Road News (an organ of China’s global strategy for infrastructure development and investments in nearly 70 countries and international organisations), Nicholas Wright, a medical doctor and neuroscientist who works on emerging technologies and global strategy at University College London, the New America think-tank and the Georgetown University Medical Center, argued that one of the significant ‘legacies’ of the coronavirus crisis will be the spread of digital surveillance enabled by artificial intelligence, and that Western liberal democracies must keep pace with East Asia.

Citing the ‘arsenal of surveillance tools’ available to the governments of China, Hong Kong, South Korea and Taiwan to track and monitor their populations — which include the mass surveillance of mobile phone, rail, and flight data; deploying hundreds of thousands of neighbourhood monitors to log the movements and temperatures of individuals; integrating health and other databases so that hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies can access the travel information of their patients; tracking down individuals suspected of being infected by looking at credit card transactions and CCTV footage; enforcing self-quarantine through a location-tracking smartphone app; requiring government-issued identity cards in order to buy SIM cards or tickets on state-run rail companies and airlines; employing colour-coded smartphone apps that tag people as green, and therefore free to travel through city checkpoints, or as orange or red, and subject to restrictions on movement; and using facial recognition algorithms to identify commuters who aren’t wearing a mask or who aren’t wearing one properly — Wright argued that:

‘Western democracies must rise to meet the need for “democratic surveillance” to protect their own populations. One of COVID-19’s most important long-term impacts will be the reshaping of digital surveillance across the globe, prompted by the public health need to more closely monitor citizens.

‘Just as the September 11 attacks ushered in new surveillance practices in the United States, the coronavirus pandemic might do the same for many nations around the world. Afflicted countries are all eager to better control their citizens. Every functioning state now has a public health strategy to tackle COVID-19 that emphasises both monitoring residents and trying to influence their behaviour.

‘Western liberal democracies must be unafraid in trying to sharpen their powers of surveillance for public health purposes. There is nothing oxymoronic about the idea of “democratic surveillance”.’

5. Civil Disobedience

Many of us strongly disagree. In opposition to this dystopian vision of a surveillance state envisaged, significantly, not by an agent of the UK’s security forces but by a member of the medical profession, I recall the recent words of the Italian philosopher of bio-politics, Giorgio Agamben, who in one of his commentaries on the Italian Government’s use of the coronavirus to implement a surveillance state under a permanent state of emergency, reminded us that:

‘A rule which states that good must be renounced in order to save the good is just as false and contradictory as that which, in order to protect freedom, orders us to renounce freedom.’

The decision of a UK citizen to comply with the Government’s attempt to enforce the wearing of masks in public is not a private decision, therefore, but a political one that affects all of us, and we must oppose it individually and collectively with mass demonstrations of non-compliance. I hope that UK citizens will unite in civil disobedience to this unjustified, disproportionate and unlawful violation of our human rights, and refuse either to wear a mask or to pay the fixed penalty notice for not doing so.

The UK Government has announced that it is in the process of rolling out a joint private-public system of biosecurity that will extend the existing emergency period for years, and most likely for the rest of our lives. We have a very small window of opportunity to stop this while there is still some doubt and anger in the public’s mind about what the Government has done to the country, and the programme to test and trace us is still in development. As I have written elsewhere, once it’s up and running, the very notion of human rights will effectively be over. Either we do what the Government tells us, or our individual access to public life, spaces and services will be removed. The mandatory wearing of masks on public transport is a test of our compliance to such forms of control; but over the past four months the UK Government has been repeatedly testing the British public for how much loss of liberty we will accept — whether it’s house arrest, enforced social distancing, sharing our medical data with private corporations, moving further education online, digitally tracking our movements and contacts, requiring biometric immunity passports to access public spaces, or imposing curfews — and at every test we have failed. This passive acquiescence and total lack of resistance must stop now.

If enough of us take a stand against this further unnecessary encroachment on our civil liberties, we can look forward to thousands of court cases in which the Crown Prosecution Service will have to prove the scientific validity of wearing masks to combat a virus that has been circulating in the UK for at least 5 months now. To this end, I hope both human rights lawyers (with Doughty Street Chambers having already published advice on challenging the thousands of unlawful arrests, prosecutions and fines issued by the police for not obeying Government guidelines) and medical practitioners will step forward to support us in challenging the Government’s right to enforce a permanent programme of bio-security on the UK population under the guise of protecting us from COVID-19. If we don’t, this will not be the last so-called emergency measure imposed on the British public under the cloak of the coronavirus crisis. Now more than ever, we must stand up to the propaganda and lies of this Government.

Appendix: Medical Advice against Wearing Masks

Below is a chronologically arranged (with the most recent first) compendium of medical opinion and advice against the use of masks, both medical and hand-made, by members of the public in non-healthcare settings. These opinions include not only the repeated statements to this effect by the World Health Organisation but also those of the UK Government’s own Scientific Advisory Group on Emergencies (SAGE) and the Deputy Chief Medical Officer for England. There is, admittedly, medical opinion in favour of using masks, much of it made following the announcement of the Government guidance making it mandatory, but these already have widespread dissemination in our national press and media. The purpose of this compendium is to arm those who have decided to ignore these guidelines with medical opinions and arguments in support of their civil disobedience.

Use of N95, Surgical, and Cloth Masks to Prevent COVID-19 in Health Care and Community Settings: Living Practice Points From the American College of Physicians

‘ACP [American College of Physicians] discourages the use of N95 respirators by asymptomatic or symptomatic persons in community settings to reduce the risk for SARs-CoV-2 infection in the absence of any demonstrated benefit.

‘Potential harms associated with mask use include self-contamination, breathing difficulties, and a false sense of security that could potentially detract from taking other precautions, such as physical distancing.

‘The goal of using N95 respirators, surgical masks, or cloth masks is to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection from asymptomatic or symptomatic infected persons to uninfected persons (source control). Currently, no direct evidence exists for the effectiveness or comparative effectiveness of various types of respirators or masks for preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection in community settings.

‘N95 respirators should not be used in a community setting, given the absence of demonstrated benefit, the possible harm with improper use (that is, the requirement for fit testing), and the global shortage of N95 respirators.’

— 18 June, 2020

Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19

‘At the present time, the widespread use of masks by healthy people in the community setting is not yet supported by high quality or direct scientific evidence and there are potential benefits and harms to consider (see below).

Potential benefits/advantages

‘The likely advantages of the use of masks by healthy people in the general public include:

reduced potential exposure risk from infected persons before they develop symptoms;

reduced potential stigmatization of individuals wearing masks to prevent infecting others (source control) or of people caring for COVID-19 patients in non-clinical settings;

making people feel they can play a role in contributing to stopping spread of the virus;

reminding people to be compliant with other measures;

potential social and economic benefits. Amidst the global shortage of surgical masks and PPE, encouraging the public to create their own fabric masks may promote individual enterprise and community integration. Moreover, the production of non-medical masks may offer a source of income for those able to manufacture masks within their communities. Fabric masks can also be a form of cultural expression, encouraging public acceptance of protection measures in general. The safe re-use of fabric masks will also reduce costs and waste and contribute to sustainability.’

Potential harms/disadvantages

‘The likely disadvantages of the use of mask by healthy people in the general public include:

potential increased risk of self-contamination due to the manipulation of a face mask and subsequently touching eyes with contaminated hands;

potential self-contamination that can occur if non- medical masks are not changed when wet or soiled. This can create favourable conditions for microorganism to amplify;

potential headache and/or breathing difficulties, depending on type of mask used;

potential development of facial skin lesions, irritant dermatitis or worsening acne, when used frequently for long hours;

difficulty with communicating clearly;

potential discomfort;

a false sense of security, leading to potentially lower adherence to other critical preventive measures such as physical distancing and hand hygiene;

poor compliance with mask wearing, in particular by young children;

waste management issues; improper mask disposal leading to increased litter in public places, risk of contamination to street cleaners and environment hazard;

difficulty communicating for deaf persons who rely on lip reading;

disadvantages for or difficulty wearing them, especially for children, developmentally challenged persons, those with mental illness, elderly persons with cognitive impairment, those with asthma or chronic respiratory or breathing problems, those who have had facial trauma or recent oral maxillofacial surgery, and those living in hot and humid environments.’

— World Health Organisation (5 June, 2020)

Expert reaction to mandatory face masks on public transport

‘The World Health Organisation’s advice is clear. Although a medical mask can offer some protection, the use of masks in a community setting is not supported. Furthermore, mask wearing can result in a false sense of security, and enhanced risks that come from touching the face. This seems to me to be another political decision, rather than one based on scientific evidence.’

— Professor Nicola Stonehouse, Professor of Molecular Virology, University of Leeds (4 June, 2020)

‘The issue of face coverings in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic is very controversial. While no ad-hoc studies with a correct design have been carried out, it is now commonly accepted that face coverings provide very little protection, if any. However, there are many potential side effects of face coverings from a clinical and epidemiological point of view, although none of them has been studied.

‘Will more people use the tube/buses because they will feel more secure given that everybody wears a face covering? This will increase the risk of transmission.

‘Will people be able not to contaminate their hands and the handrails by not touching their face coverings and not touching the handrails while standing inside buses and trains? This seems to be impossible to me. Face coverings can therefore be a vehicle of infection, rather than a barrier.’

— Dr. Antonio Lazzarino, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London

‘This policy will add more burden on the general public to prevent the spread of COVID-19. This is much more complicated than “wash your hands for 20 seconds” or “stay at home”. We are asking the whole population of Britain, with no prior experience of mask-wearing, to overnight become competent makers, wearers, and maintainers of PPE. I hope the Government has a fool-proof plan in place to educate every family in the country on how to do this, or it could actually put people at higher risk of infection.

‘Wearing a basic face mask does little or very little to prevent the wearer from getting infected by others, but there is some limited evidence that wearing one can prevent others from being infected by the wearer. I have seen no new evidence to suggest why the Government is reversing its previous policy, and ignoring its previous scientific guidance and the guidance of the WHO. I’m left wondering if this is a political decision, rather than one based on science.

‘If this change in policy is to be successful at reducing infections, it will have to be accompanied by a major new campaign to educate 66 million people on how to properly make, put on, handle and clean their face coverings. A badly-fitted, damp or dirty mask, or poor habits such as regularly touching eyes or adjusting the ties, can put the wearer at greater risk of infection.’

— Dr Simon Clarke, Associate Professor in Cellular Microbiology, University of Reading (4 June, 2020)

Nonpharmaceutical Measures for Pandemic Influenza in Nonhealthcare Settings — Personal Protective and Environmental Measures

‘Disposable medical masks (also known as surgical masks) are loose-fitting devices that were designed to be worn by medical personnel to protect accidental contamination of patient wounds, and to protect the wearer against splashes or sprays of bodily fluids. There is limited evidence for their effectiveness in preventing influenza virus transmission either when worn by the infected person for source control or when worn by uninfected persons to reduce exposure. Our systematic review found no significant effect of face masks on transmission of laboratory-confirmed influenza.

‘We did not consider the use of respirators in the community. Respirators are tight-fitting masks that can protect the wearer from fine particles and should provide better protection against influenza virus exposures when properly worn because of higher filtration efficiency. However, respirators work best when they are fit-tested, and these masks will be in limited supply during the next pandemic. These specialist devices should be reserved for use in healthcare settings or in special subpopulations such as immunocompromised persons in the community, first responders, and those performing other critical community functions, as supplies permit.

‘In lower-income settings, it is more likely that reusable cloth masks will be used rather than disposable medical masks because of cost and availability. There are still few uncertainties in the practice of face mask use, such as who should wear the mask and how long it should be used for. In theory, transmission should be reduced the most if both infected members and other contacts wear masks, but compliance in uninfected close contacts could be a problem. Proper use of face masks is essential because improper use might increase the risk for transmission.’

— Centers for Disease Control and Infection (May 2020)

Universal Masking in Hospitals in the Covid-19 Era

‘We know that wearing a mask outside health care facilities offers little, if any, protection from infection. Public health authorities define a significant exposure to Covid-19 as face-to-face contact within 6 feet with a patient with symptomatic Covid-19 that is sustained for at least a few minutes (and some say more than 10 minutes or even 30 minutes). The chance of catching Covid-19 from a passing interaction in a public space is therefore minimal. In many cases, the desire for widespread masking is a reflexive reaction to anxiety over the pandemic.’

— New England Journal of Medicine (21 May, 2020)

Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19 in Europe: a quasi-experimental study

‘The use of face coverings initially seems to have had a protective effect. However, after day 15 of the face covering advisories or requirements, the number of cases started to rise. Similar patterns were observed for the relationship between face coverings and deaths. Negative associations were estimated for mass gatherings, initial business closure and the closure of educational facilities; while a non-significant effect was estimated for non-essential business closure. There was a positive association with the usage of face coverings (masks), while the stay-home measures showed an inverted U quadratic effect with an initial rise of cases up to day 20 of the intervention followed by a decrease in cases. These results would suggest that the widespread use of face masks or coverings in the community do not provide any benefit. Indeed, there is even a suggestion that they may actually increase risk, but as stated previously, we feel that the data on face coverings are too preliminary to inform public policy.’

— Professor Paul Raymond Hunter, Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia; Dr. Julii Suzanne Brainard, University of East Anglia; Dr. Felipe Colon-Gonzalez, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; Dr. Steve Rushton, University of Newcastle (6 May, 2020)

Community face mask use

‘The evidence on effectiveness of mask for source control (i.e. stopping infectious people — pre-symptomatic/asymptomatic — from infecting others) is weak. Evidence for protecting the mask wearer from becoming infected is also weak.

‘The effect of wearing a mask is likely to be small but not zero. The RCT [randomised clinical trial] evidence is weak and it would be unreasonable to claim a large benefit from wearing a mask.

‘SAGE advice below refers to cloth masks — specifically in the context of lockdown measures.

‘Negative behavioural impacts cannot be ruled out, e.g. those with symptoms who should isolate instead choose to break quarantine wearing a mask, or repeated handling of mask could increase hand-face contact.

‘Wearing masks in the context of lifting NPIs [non-pharmaceutucal interventions] could reduce anxiety about release of emasures, or reinforce the need for distancing measures.’

— Minutes of the 27th meeting of the Scientific Advisory Group on Emergencies (21 April, 2020)

Do face masks work? A note on the evidence

‘When a person is infectious with a virus it is estimated that they may shed one hundred billion virus particles a day — that works out at about ten million per breath. A mask won’t stop you putting these particles into the air around you. In fact, with a damp mask you’ll be blowing aerosols and larger particles sideways, directly at your socially distanced colleagues two metres away. And if wearing a mask tempts you to feel that you’re not going to infect anyone else, you may also be less likely to observe the two-metre rule. So does wearing a mask protect others if you’re infectious? There’s little direct evidence to say that it does, and quite a lot of straightforward reasoning to suggest it doesn’t.’

‘The point is: does any of what is out there add up to a watertight case for compelling people to wear masks in public or at work (outside a healthcare setting)? The threshold for compulsion must surely be higher than ‘maybe’ and ‘perhaps’. But if it really is the case that the threshold for regulatory compulsion is being approached, it should be a simple matter for our scientific advisors to present it to us and allow time for it to be critically discussed in relation to a real-world setting, before Government imposes measures upon us all. That other countries may have taken action says things about those countries’ attitudes to open scrutiny of evidence-based decision-making, and their populations’ attitudes to compliance and compulsion. It says nothing about the validity of the measures.’

— Dr. John Lee, former professor of pathology and NHS consultant pathologist (19 April, 2020)

Masks Don’t Work: A review of science relevant to Covid-19 social policy

‘Masks and respirators do not work. There have been extensive randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies, and meta-analysis reviews of RCT studies, which all show that masks and respirators do not work to prevent respiratory influenza-like illnesses, or respiratory illnesses believed to be transmitted by droplets and aerosol particles.

‘Furthermore, the relevant known physics and biology, which I review, are such that masks and respirators should not work. It would be a paradox if masks and respirators worked, given what we know about viral respiratory diseases: The main transmission path is long-residence-time aerosol particles (<2.5μm), which are too fine to be blocked, and the minimum-infective-dose is smaller than one aerosol particle.

‘The present paper about masks illustrates the degree to which governments, the mainstream media, and institutional propagandists can decide to operate in a science vacuum, or select only incomplete science that serves their interests. Such recklessness is also certainly the case with the current global lockdown of over 1 billion people, an unprecedented experiment in medical and political history.’

— D. G. Rancourt, Ontario Civil Liberties Association, former tenured and Full Professor of physics at the University of Ottawa, Canada (11 April, 2020)

Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19

‘There is limited evidence that wearing a medical mask by healthy individuals in the households or among contacts of a sick patient, or among attendees of mass gatherings may be beneficial as a preventive measure. However, there is currently no evidence that wearing a mask (whether medical or other types) by healthy persons in the wider community setting, including universal community masking, can prevent them from infection with respiratory viruses, including COVID-19.

‘The wide use of masks by healthy people in the community setting is not supported by current evidence and carries uncertainties and critical risks. WHO stresses that it is critical that medical masks and respirators be prioritized for health care workers. The use of masks made of other materials (e.g., cotton fabric), also known as nonmedical masks, in the community setting has not been well evaluated. There is no current evidence to make a recommendation for or against their use in this setting.’

— World Health Organisation (6 April 2020)

Effectiveness of Surgical and Cotton Masks in Blocking SARS–CoV-2: A Controlled Comparison in 4 Patients

‘Neither surgical nor cotton masks effectively filtered SARS–CoV-2 during coughs by infected patients. Prior evidence that surgical masks effectively filtered influenza virus informed recommendations that patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 should wear face masks to prevent transmission. However, the size and concentrations of SARS–CoV-2 in aerosols generated during coughing are unknown. Oberg and Brousseau demonstrated that surgical masks did not exhibit adequate filter performance against aerosols measuring 0.9, 2.0, and 3.1 μm in diameter. Lee and colleagues showed that particles 0.04 to 0.2 μm can penetrate surgical masks. The size of the SARS–CoV particle from the 2002–2004 outbreak was estimated as 0.08 to 0.14 μm; assuming that SARS-CoV-2 has a similar size, surgical masks are unlikely to effectively filter this virus.

‘This experiment did not include N95 masks and does not reflect the actual transmission of infection from patients with COVID-19 wearing different types of masks. We do not know whether masks shorten the travel distance of droplets during coughing. Further study is needed to recommend whether face masks decrease transmission of virus from asymptomatic individuals or those with suspected COVID-19 who are not coughing.

‘In conclusion, both surgical and cotton masks seem to be ineffective in preventing the dissemination of SARS–CoV-2 from the coughs of patients with COVID-19 to the environment and external mask surface.’

— Annals of Internal Medicine (6 April, 2020). This article was subsequently withdrawn at the request of the editors.

Masks-for-all for COVID-19 not based on sound data

‘We do not recommend requiring the general public who do not have symptoms of COVID-19-like illness to routinely wear cloth or surgical masks because:

There is no scientific evidence they are effective in reducing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission;

Their use may result in those wearing the masks to relax other distancing efforts because they have a sense of protection;

We need to preserve the supply of surgical masks for at-risk healthcare workers.

‘Sweeping mask recommendations — as many have proposed — will not reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission, as evidenced by the widespread practice of wearing such masks in Hubei province, China, before and during its mass COVID-19 transmission experience earlier this year. Our review of relevant studies indicates that cloth masks will be ineffective at preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission, whether worn as source control or as PPE.

‘We realize that the public yearns to help protect medical professionals by contributing homemade masks, but there are better ways to help.

‘Given the paucity of information about their performance as source control in real-world settings, along with the extremely low efficiency of cloth masks as filters and their poor fit, there is no evidence to support their use by the public or healthcare workers to control the emission of particles from the wearer.

‘Leaving aside the fact that they are ineffective, telling the public to wear cloth or surgical masks could be interpreted by some to mean that people are safe to stop isolating at home. It’s too late now for anything but stopping as much person-to-person interaction as possible.

‘Masks may confuse that message and give people a false sense of security. If masks had been the solution in Asia, shouldn’t they have stopped the pandemic before it spread elsewhere?

‘For readers who are disappointed in our recommendations to stop making cloth masks for themselves or healthcare workers, we recommend instead pitching in to locate N95 FFRs and other types of respirators for healthcare organizations. Encourage your local or state government to organize and reach out to industries to locate respirators not currently being used in the non-healthcare sector and coordinate donation efforts to frontline health workers.’

— Centre for Disease Research and Policy (1 April, 2020)

COVID-19, shortages of masks and the use of cloth masks as a last resort

Critical shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) have resulted in the US Centers for Disease Control downgrading their recommendations for health workers treating COVID-19 patients from respirators to surgical masks and finally to home-made cloth masks. As authors of the only published randomised controlled clinical trial of cloth masks, we have been getting daily emails about this from health workers concerned about using cloth masks. The study found that cloth mask wearers had higher rates of infection than even the standard practice control group of health workers, and the filtration provided by cloth masks was poor compared to surgical masks.

— British Medical Journal (30 March, 2020)

Face masks could increase risk of infection

‘For the average member of the public wandering down a street this is really not a good idea. What tends to happen is people will have one mask. They won’t wear it all the time. They will take it off when they get home. They’ll put it down on a surface they haven’t cleaned. Or they will be out — they haven’t washed their hands — and they’ll go and have a cup of coffee somewhere. They half hook it off, they wipe something over it, they’ll put it back on. And, in fact, you can actually trap the virus in the mask and start breathing it in. Because of these behavioural issues, which are really important when talking about infectious diseases, people can adversely put themselves at more risk than less.’

— Dr. Jenny Harries, Deputy Chief Medical Officer for England (12 May, 2020)

Non-pharmaceutical public health measures for mitigating the risk and impact of epidemic and pandemic influenza

‘There is a moderate overall quality of evidence that face masks do not have a substantial effect on transmission of influenza.

‘Face mask use is common to prevent transmission of infections in health care settings around the world, and a widely used measure in some communities, particularly in South-East Asia.

‘Reusable cloth face masks are not recommended. Medical face masks are generally not reusable, and an adequate supply would be essential if the use of face masks was recommended. If worn by a symptomatic case, that person might require multiple masks per day for multiple days of illness.’

— World Health Organisation (October 2019)

Why face masks don’t work: A revealing review

‘The science regarding the aerosol transmission of infectious diseases has, for years, been based on what is now appreciated to be “very outmoded research and an overly simplistic interpretation of the data”. Modern studies are employing sensitive instruments and interpretative techniques to better understand the size and distribution of potentially infectious aerosol particles.

‘It should be concluded from these and similar studies that the filter material of face masks does not retain or filter out viruses or other submicron particles. When this understanding is combined with the poor fit of masks, it is readily appreciated that neither the filter performance nor the facial fit characteristics of face masks qualify them as being devices which protect against respiratory infections.

‘Between 2004 and 2016 at least a dozen research or review articles have been published on the inadequacies of face masks. All agree that the poor facial fit and limited filtration characteristics of face masks make them unable to prevent the wearer inhaling airborne particles. In their well-referenced 2011 article on respiratory protection for healthcare workers, Drs. Harriman and Brosseau conclude that “facemasks will not protect against the inhalation of aerosols.”

‘The primary reason for mandating the wearing of face masks is to protect dental personnel from airborne pathogens. This review has established that face masks are incapable of providing such a level of protection. Unless the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, national and provincial dental associations and regulatory agencies publically admit this fact, they will be guilty of perpetuating a myth which will be a disservice to the dental profession and its patients.’

— John Hardie, BDS, MSc, PhD, FRCDC, Oral Health (18 October, 2016). Like so much published online that contradicts Government policy, this article has since been removed from its original location on the internet, but it can still be accessed here: Why face masks don’t work.

A cluster-randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers

‘This study is the first RCT [randomised clinical trial] of cloth masks, and the results caution against the use of cloth masks. This is an important finding to inform occupational health and safety. Moisture retention, reuse of cloth masks and poor filtration may result in increased risk of infection. Further research is needed to inform the widespread use of cloth masks globally.’

— British Medical Journal (2015)

If you know of additional medical advice against the wearing of hand-made masks by the public, please copy a link in the comments section below and I will add it to this compendium.

Addendum: New Legislation on Wearing Masks

As the Government indicated to the public on 12 June, a mere 3 days before it came into force, a statutory instrument was today made into law under the emergency procedure set out in Section 45R of the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984. This is the latest of the 102 coronavirus-related statutory instruments laid before Parliament; and in accordance with this legislation on ‘emergency procedure’, the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Wearing of Face Coverings on Public Transport) (England) Regulations 2020 were made without a draft having been laid before and approved by a resolution of each House of Parliament. The reason given for this circumvention of the legislature, as it was for the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020 (the Regulations) that came into force on 26 March, is as follows:

‘It is the opinion of the Secretary of State that, by reason of urgency, it is necessary to make the order without a draft being so laid and approved so that public health measures can be taken in response to the serious and imminent threat to public health which is posed by the incidence and spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).’

It is unclear how, 3 months after social distancing guidelines were issued by the Government on 16 March and the subsequent lockdown of the UK was imposed on 23 March, there can be sufficient urgency and insufficient time to justify circumventing scrutiny and approval by our elected representatives in Parliament of Regulations on a policy that has been considered by the Government for months and will now be imposed by UK police forces on tens of millions of British citizens. Just as it is unclear how the present situation constitutes a ‘serious and imminent threat to public health’ when, between 25 May and 7 June, the National Office for Statistics estimated just 0.06 per cent of the population in England, or 1 in 1,700 people, were infected with SARs-CoV-2; when, by 9 June, the NHS reported that only 294 people under the age of 60 without pre-existing medical conditions had died in English hospitals with their deaths attributed to COVID-19; when, the day before these Regulations were published, the Government itself attributed just 36 deaths to COVID-19; and the Government’s own estimated rate of reproduction for every person infected in the UK is between 0.2 and 0.7. But without providing evidence of either their justification or proportionality, these Regulations:

Come into force on 15th June 2020, and apply to English land, sea and airspace.

Defines a ‘face covering’ as anything that covers a person’s nose and mouth, the mandatory wearing of which applies on public transport, excluding school transport, taxis or private hire and cruise ships.

Prohibits any person, without ‘reasonable excuse’, from using public transport without wearing a face covering. This does not include any child under 11 years of age; any employee of the operator of the relevant public transport service in the course of their employment; a constable or police community support officer acting in the course of their duty; an emergency responder; a relevant official; or anyone in an enclosed cabin, berth or car on a ship who is alone or with members of the same household.

Defines a reasonable excuse as any physical or mental illness or impairment, or disability; or severe distress caused by wearing a face covering; or travelling with someone who relies on lip reading to communicate; or to avoid harm or injury; or in order to eat or drink; or to take medication; or upon direction by a ‘relevant person’.

Defines a relevant person as a police constable; a police community support officer; or a public transport officer, employee or agent authorised by the operator for the purposes of this regulation. This Regulation empowers such persons to deny boarding of a vehicle providing a public transport service to a person not wearing a face covering; to direct a person either to wear a face covering or to disembark from a relevant vehicle. It additionally empowers a constable to remove a passenger from a relevant vehicle, using reasonable force if necessary, if they fail to comply with a direction to disembark from the vehicle. Imprtantly, the ‘Explanatory Memorandum’ to the Regulations adds that operators of public transport services ‘have discretion over whether they choose to use these powers; they do not have an obligation to do so’.

Provides that any person who contravenes this regulation commits an offence, which is punishable by a fine.

Empowers a fixed penalty notice, which enables a person to discharge their liability to criminal conviction, to be issued by a constable, police community support officer, a Transport for London officer, or any person designated by the Secretary of State for the purposes of this regulation, such as an operator of a public transport service. The fixed penalty notice can be issued to a person over 18 years of age whom such a person reasonably believes to have committed an offence under these Regulations. The amount of the fixed penalty is £100, reduced to £50 if paid within 14 days of a notice being issued.

Empowers the Crown Prosecution Service and any person designated by the Secretary of State to bring proceedings for an offence under these Regulations.

Requires the Secretary of State to review the need for the requirements imposed by the Regulations before the end of the period of 6 months, beginning with the day on which they come into force.

Provides that these Regulations cease to have effect at the end of the period of 12 months, beginning with the day on which they come into force.

Despite an assessment of their impact not having been made, the Secretary of State for Transport has nonetheless said that, in his view, these Regulations are ‘compatible’ with the European Convention on Human Rights.

He does not explain why, however, the general public are considered potential transmitters of SARs-CoV-2 of a sufficient degree of virulence to require the compulsory wearing of masks on public transport, and yet the constables, community support officers and transport staff tasked with policing the public every day, and therefore the most obvious source of viral contagion, are not.

Nor does he explain why, given the £100 fixed penalty notice for diosobedience, a wealthier person should be more financially able to ignore these Regulations compared to a poorer person, implying that such a person represents less of a threat to public health.

Nor does he explain whether a person must prove their ‘severe distress caused by wearing a face covering’ to a constable, community support officer or other relevant person, and if so how.

Nor does he accept any legal responsibility, or indicate any commitment to financial compensation, for loss of life, or work or employment for anyone who — as is suggested by the numerous medical opinions quoted above — contracts SARs-CoV-2 or some other respiratory disease, or is exposed to any other medical complications, caused by breathing though and into the type of home-made masks they are compelled by these Regulations to wear on a daily basis and for extended periods of time in the enclosed and often humid environments that characterise public transport in the UK and particularly in London during the summer.

As serious, perhaps, as this cavalier and arbitrarily imposed approach to the health and safety of passengers on UK public transport is the fact that these Regulations have only been published on the day on which they come into effect, without assessment, scrutiny, debate or approval, thereby ignoring the division of powers — executive, legislature and judiciary — on which we rely for the democratic accountability of government. This has characterised and defined the huge number and reach of powers made by the Government under the cloak of the coronavirus crisis, and its latest use to impose politically motivated and medically unsubstantiated and even dangerous regulations indicates how the Government will roll out the even greater violations of our human rights and civil liberties by future programmes such as contact tracing, immunity passports and vaccination, which truly do present a ‘serious and imminent threat’ to the UK public.

Just five days ago, on 10 June, at the Fourth Delegated Legislation Committee to discuss the second amendment to the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) (Amendment) (No. 2) Regulations 2020, Justin Madders, the Member of Parliament for Ellesmere Port and Neston, questioned the Minister for Care, Helen Whately, about the procedure for considering these regulations. Pointing out that these were signed into law several weeks before, he made the following criticisms, which I will quote at length, not least because this is one of the very few examples of which I am aware of our elected representatives in Parliament attempting to hold the Government to account over its repeated and ongoing circumvention of parliament scrutiny of coronavirus legislation:

‘The Minister has said that it is right that the rule of law be maintained, and of course we agree with that, but I fear that, by debating these regulations retrospectively, we are treading on the wrong side of that. As I stated when we debated those initial regulations back on 4 May — some six weeks after they had been introduced — given that Parliament was up and running again by that time, there should have been sufficient time to ensure that future changes were debated and had democratic consent before they were introduced. Debating them weeks after the event, and when in fact they have already been superseded, as we have heard today, is frankly an insult.

‘There is no excuse for this situation now. As we have heard, the regulations require there to be a review every three weeks, as the Secretary of State has a duty to terminate any regulations that are not necessary or proportionate to control the transmission of the virus. That means that all along we have had a clear timetable and sight for when new regulations might be created, which should have allowed plenty of opportunity for parliamentary scrutiny of those regulations.

‘Yet here we are again today, debating regulations that came into effect weeks ago. That is not good enough. Moving forwards, we cannot carry on in this way and the Government accept our indolence at their peril. Does the Minister agree that debating regulations when they are already out of date makes a mockery of the process?

‘The Minister went on to say that the regulations are, in fact, constantly reviewed; I should be grateful if she would clarify exactly what she means by that. Is there a formal process by which that is taking place, or are there, in fact, just the three-weekly reviews that have been set out in the regulations?

‘As for those reviews, where are they? In a written question that I put to the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, I asked if he would publish the reviews carried out on 16 April, 7 May and 28 May pursuant to these regulations. I received a reply to that question at half-past 9 last night, which said:

“The Department of Health and Social Care has indicated that it will not be possible to answer the question within the usual time period.”

‘I find that absolutely incredible, and, regrettably, the failure of the Department to provide me with an answer to what I would have thought was a pretty important and obvious question leads me to one inevitable and damning conclusion: there has been no proper review.

‘Here we have the most far-reaching impositions on the life of this country in peacetime, and the Government has not, as required by law, conducted any review of those regulations that we can actually see; or if they have, they have decided that we do not deserve to see them, which is equally reprehensible.

‘I understand, from what the Minister said in her introduction, that there were several more reviews on 22 April and 7 May. Again, if the Minister had not been good enough to tell us today about those reviews, we would never have known that they had taken place. We need far more transparency than we are seeing at the moment. We cannot go on like this.

‘It is because of their wide-ranging effect that these measures demand full parliamentary scrutiny. I am sure that many hon. Members agree that a 90-minute debate by a small parliamentary Committee, weeks after the fact, cannot possibly be sufficient to provide the level of examination and scrutiny that such important laws require. As we have seen, great efforts have been made by staff to get Parliament up and running again. We should not demean those efforts by turning these debates into a procedural formality, a rubber-stamping exercise to create the veneer of a democratic process. We should be better than that. We should not be debating the measures late and without the full extent of the information on which the Government have made their decisions.

‘When it comes to the regulations themselves, not only has the legally required review of them not been disclosed to date; they have not had any kind of impact assessment carried out. Again, to be fair to the Government, we understand why, in the first instance, that was not possible. However, we did make it very clear, the last time the regulations were debated, that we did not want that to become the norm, especially for regulations such as these, where we know that the impact will have been huge. The second and third set of regulations have apparently had no impact assessment, either. How can the Government continue to issue new laws with such sweeping powers as these when they cannot tell us what their impact is?’

As the latest instance of the ongoing making of the most draconian and intrusive laws in the history of the UK during peacetime, the unjustified and grossly disproportionate Health Protection (Coronavirus, Wearing of Face Coverings on Public Transport) (England) Regulations 2020 raise further questions for the legislature, judiciary and UK public about our ability to hold the executive to account under an ‘emergency period’ it is in the Government’s power to extend indefinitely. With public protests banned under the third amendment to the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) (Amendment) (No. 3) Regulations 2020 that came into force on 1 June and were approved by a virtual Parliament on 15 June; with the UK press and media embracing its role as an organ of Government propaganda devoted to spreading fear and silencing questions; with the Government free to make laws without parliamentary approval; with the UK judiciary silent and complicit in enacting these laws; with legislative procedures of review not being followed in any meaningful and accountable way; and with what scrutiny a virtual Parliament can attempt either ignored or dismissed by Ministers; we are, technically speaking — which is to say, in political terms — living under a legislative dictatorship.

Simon Elmer

Architects for Social Housing

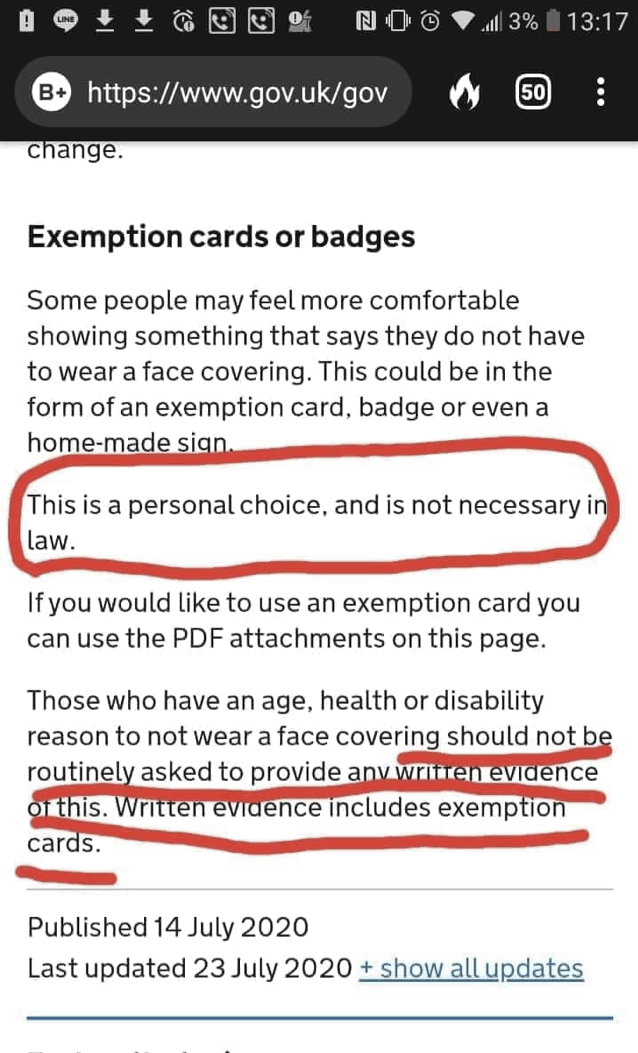

Postscript. In the absence of either legislation or Government guidance on whether a person has to prove they have a ‘reasonable excuse’ for exemption from these Regulations — and if so how — in order to avoid a fixed penalty notice of £100 from a constable, community support office, Transport for London officer, employee or agent of a transport service operator, or any relevant person designated by the Secretary of State to impose these Regulations, I wrote to Transport for London — which has the discretion and not the obligation to use these powers — and in return was advised that on Friday, 19 June, TfL had introduced an ‘exemption card’ that customers of their services can either print out and carry or download onto their phone and produce on request, granting them exemption. The pdf for these cards is available on the TfL website page ‘Face coverings’. If challenged by a relevant person, and in the absence of any medical reason or duty of care, someone not wishing to travel on public transport with a covering over their face can state that, under Section 4, a), ii of the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Wearing of Face Coverings on Public Transport) (England) Regulations 2020, he or she is exempt because wearing such a covering causes them ‘severe distress’. If asked what the nature of this distress is, they might wish to direct the relevant person to the contents of this article.

Further reading by the same author:

Lockdown: Collateral Damage in the War on COVID-19

The State of Emergency as Paradigm of Government: Coronavirus Legislation, Implementation and Enforcement

Manufacturing Consensus: The Registering of COVID-19 Deaths in the UK

Giorgio Agamben and the Bio-Politics of COVID-19

Good Morning, Coronazombies! Diary of a Bio-political Crisis Event

Coronazombies! Infection and Denial in the United Kingdom

Language is a Virus: SARs-CoV-2 and the Science of Political Control

Sociology of a Disease: Age, Class and Mortality in the Coronavirus Pandemic

COVID-19 and Capitalism

Architects for Social Housing is a Community Interest Company (no. 10383452). This is a stupendous article replete with excellent references - please feel minded to support this independent effort for clarity, fact and information. If you would like to support their work financially, please make a donation through PayPal: